Originally published by The News Tribune, November 3rd, 2024. Written by Craig Sailor.

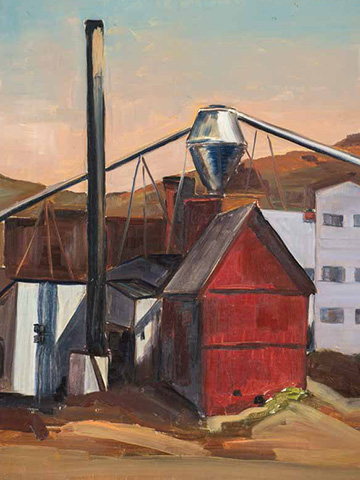

Tacoma painter Beulah Loomis Hyde wasn’t content to paint sunsets, flowers and the pretty pictures her contemporaries did in the 1930s and 1940s. She turned her easel toward the city’s factories, shipyards, bridges and Hoovervilles.

Today, the city’s history is all the richer for it.

Acclaimed regionally at the time, Hyde was all but forgotten after the 96-year-old artist died in 1983.

Now, a show at Cascadia Art Museum in Edmonds offers a first of its kind retrospective of her career. The vast majority of the canvases in the show were painted in Tacoma. They were gathered from her descendants from around the world.

“When I saw the quality of her work, I was bowled over,” said David Martin, the museum’s curator and organizer of “Structure and Form — The Art of B.L. Hyde.”

Martin has long had an interest in shinning a light on the overlooked female artists who populated the Pacific Northwest in the early and mid-20th century.

The more than 50 paintings in the show time travel to Tacoma when industry was king. One painting shows Galloping Gertie, the first Tacoma Narrows Bridge, which was brought down by a windstorm in 1940.

Other paintings show traffic, markets and businesses from a long-ago city. Hyde didn’t shy away from the city’s grittier side. She could paint a colorful fruit market as well as a shanty town on the Tideflats.

Beulah Hyde

Born in Kansas in 1886, Hyde moved with her family to Tacoma 1888. The impoverished family’s fortune soon turned for the better, and Hyde grew up wealthy enough to attend Annie Wright Seminary (now Schools).

Her artistic talent emerged when she was a girl. The show contains one of her early sketch books. She was influenced, taught and tutored by some of the region’s best artists, Martin said.

Hyde had two productive periods in her career. The first was from 1902 to around 1915. She took a break when she got married and began having children. In that early period, she drew in graphite and painted in watercolor.

After her three boys were grown, she took up painting again. From around 1935 to about 1960 seems to be her most productive period, Martin said.

Her second period consisted of oil paintings on canvas. Most notably, she adopted a modernist style, he said.

Painting in a man’s world

In the early 1900s, women artists weren’t given the same opportunities male artists were, Martin said.

“The compliment that you would give a woman artist back then was that they painted like a man,” he said.

Art competitions were popular in those days, and female artists would often try to hide their gender, Martin said.

“So (the judges) didn’t think, is this a woman? Or they wouldn’t be prejudice,” he said.

Tacoma’s newspapers did cover Hyde’s career. The show includes a 1947 clipping from the Tacoma Times which shows Hyde painting a canvas. A notable aspect of the clipping is the byline of the photographer who shot the photo: Frank Herbert, the author of “Dune” and other science fiction novels.

Like Hyde, Herbert grew up in Tacoma where he was influenced by pollution from the ASARCO smelter in Ruston. The smelter, spewing smokestacks, tunnels and other industry feature in many of Hyde’s paintings.

The show

After Hyde died in 1983, her work remained primarily in the collections of her descendants and unavailable to the public.

The Cascadia Art Museum focuses on Pacific Northwest Art through the 1960s, but Martin was only vaguely familiar with Hyde.

“I had seen one or two of her paintings a long time ago at the Tacoma Art Museum, and I really liked them,” he said. “They were really different than the local regional art.”

When a donor gave two of Hyde’s paintings to the museum in 2022, it piqued Martin’s interest.

Then began a exhaustive search for Hyde’s work. Several paintings are on loan from TAM. Most are from her descendants, who scattered from Lakewood to London. About half of the paintings needed restoration.

“They had been in storage, and a lot of them were covered with mold and unstretched and in rough shape,” Martin said.

Because Hyde didn’t date any of her work, he’s only been able to guess at each work’s period, based on the medium, style and subject.

Shapes, forms, color

It doesn’t take a curator to point out what drew Hyde’s eye. While there are a few portraits and still lifes in the show, her subjects consist mostly of commercial structures, often reduced to their basic shapes.

In one painting, Tacoma’s Washington Cooperative Farmers Association grain elevator on the Hylebos Waterway becomes an enormous L-shape.

Smokestacks, lumber yards, factories and grain elevators abound.

Hyde rarely gave a sense of life to her paintings, Martin said. Still, a few show smoke billowing from stacks, traffic moving on a street, clouds and waves.

Daily life

One eye-catching painting shows a Victorian home perched on a butte. It’s unknown if Hyde painted the scene from life. In the 1920s, Seattle flattened several hills by blasting them away with water in what became known as the Denny Regrade. Some property owners refused to cooperate and left “spite mounds” in the way.

One painting shows a gas station in late afternoon light, waiting for cars and customers.

Hyde didn’t too much self-promotion. Instead, she supported other artists from Tacoma, Martin said.

“She gave them shows,” he said. “She gave them money; she commissioned them.”

Martin has authored a book that accompanies the show, “Structure and Form,” which is distributed by the University of Washington Press.

You can find the original article by following this link.